Deranged, Disgusting, or Inhuman

In other words, deserving of your contempt.

(If you haven’t read Crazy, Stupid, or Awful, you might want to read that one first. Crazy, Stupid, Awful means you probably are thinking of your partner as a “Them” instead of thinking about the two of you as a “We” or an “Us,” but some careful, attentive, open listening might suffice. Like in They Might Be An Alien)

But contempt is something a little different.

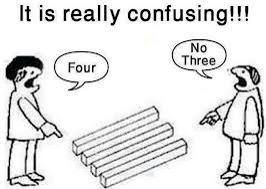

The Gottmans (e.g., Gottman, 1993) really brought the idea of contempt onto the couples’ therapy scene, a kind of relational filter that says “I’m better than you, and you don’t deserve my basic respect.” Sometimes, it looks like sarcasm or condescension (speaking as if your partner really is stupid, or worse). Sometimes, it’s withdrawal (because you believe that your partner really is disgusting and you can’t stand to be around them). Sometimes, it sounds like demeaning put-downs (because you think your partner is just a real piece of shit). It’s dehumanizing (e.g., Kteily et al., 2022). And that’s a much bigger problem than thinking they’re a decent human being who you just really don’t understand or agree with.

The impacts of contempt are probably quite a bit broader than just in couples’ relationships, too. As therapists, we need to be on the lookout for contempt of partners, but also of kids and bosses, among others. And there are some pragmatic things we need to think about – when parents are using sarcasm, condescension, demeaning put downs, and/or withdrawal/neglect with their children… we need to intervene strongly and quickly to help them make changes. Eye-rolling, name-calling, and that pinched-face look of disgust need to be taken with plenty of seriousness. When it’s someone talking about a coworker, boss, friend, etc., the easiest solution might be to simply get out of that situation or relationship… contempt (like real burnout) is pretty damn hard to come back from.

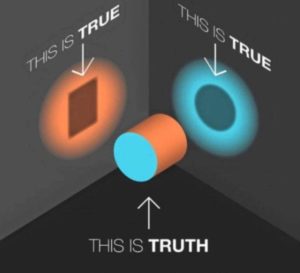

But then, we also need to look at the underlying cognitive structures that support contempt… Contempt “implies sense of superiority over [other people], pessimistic feelings about their possibility of betterment, detachment from them, and avoidance driven by detachment (Miceli & Castelfranchi, 2018). So, I’m going to go ahead and say (maybe outrageously?!) that contempt is never rational. So, to be clear, I’m not saying that anyone should stay in contact with someone they feel contempt toward. Maybe the contempt goes along with other thoughts/feelings that are quite reasonable and dictate that the appropriate behavior is detachment (e.g., an actually abusive partner, an actually unfair and unpleasant working environment). But that sense of down-to-the-ground superiority of one (aggrieved) person over another? Mmmm… that’s a tough sell for me. Dehumanizing a human being doesn’t fit the logic I understand.

And there are personality structures, too. It’s possible to have a contemptuous “personality” (or long term attributional style, maybe?). Sometimes, that goes along with narcissistic and antisocial stuff (esp when the dispositional contempt is typically outwards), but sometimes the contempt is directed inwardly at the self, as well! (see Schriber et al., 2017).

I’m sure how you choose to work on this depends on your theoretical orientation… I just wanted to take a minute to bring it to the forefront and make sure we’re not letting some important signs pass us by!

Comment below: What other markers of disgust do you see in clients? Do you ever find it easy to blow those off? How do you work with clients on these deep cognitive structures?

Gottman, J. M. (1993). A theory of marital dissolution and stability. Journal of family psychology, 7(1), 57.

Kteily, N. S., & Landry, A. P. (2022). Dehumanization: Trends, insights, and challenges. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 26(3), 222–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.12.003

Miceli, M., & Castelfranchi, C. (2018). Contempt and disgust: The emotions of disrespect. Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior, 48(2), 205-229. https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12159

Schriber, R. A., Chung, J. M., Sorensen, K. S., & Robins, R. W. (2017). Dispositional contempt: A first look at the contemptuous person. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(2), 280-309. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000101.